Harry Bertoia was a metal worker ahead of his time who crossed boundaries daily. His jewelry is sculpture you wear, the monotypes a window into the universe, the chairs are sensual and sculptural and his sculptures range from welded to spill-cast to hand-shaped. His gentle nature was expressed in delicate fine wire work while his superhuman strength was needed to handle the massive architectural commissions. He designed the ever-popular Diamond chair, crafted over 50 public sculptures, and created the Sonambient sounding sculptures. From biomorphic jewelry to 4-ton fountains, from children’s chairs to the asymmetric chaise, from singing rods to thunderous 10’ gongs, from color field graphics to layered monographics, this prolific man preferred not to title his art because it came from “the great Oneness,” and needed no man’s identification or name to have its effect.

CHILDHOOD, 1915-1930

Arri Bertoia was born on March 10, 1915, in the small village of San Lorenzo, Friuli, Italy, about 50 miles north of Venice and 70 miles south of the Austrian border. He had one older brother, Oreste, and one younger sister, Ave. Another sister, Ada, died at eighteen months old; she was the subject of one of his first paintings.

Arri, nicknamed Arieto (little Arri), attended school in nearby Arzene, Carsara, until grade 5. As a teenager, the local brides would have him to design their wedding day linen embroidery patterns, as his talents were already recognized. An art teacher from a neighboring town proffered a few drawing lessons, but soon told his parents that Harry was too talented for him to teach him anything else. He suggested further training in art, perhaps in Venice or maybe America? Harry, at age 15, was presented with a daunting decision.

MOVE TO AMERICA, 1930

In 1930 Harry chose to move to Detroit where his brother Oreste was already established. Upon entering North America, his name Arri was altered to the Americanized Harry. He learned English and history and a smattering of American customs at the Davison Americanization School. Other lessons, many by trial and error, involved using public transport and learning how to navigate museums.

Bertoia attended Cleveland Public Intermediate School to catch up in basics from 1931 – 1935. He then entered Cass Technical High School in 1935, a public school with a special program for talented students in arts and sciences. In 1936, a one-year scholarship to the School of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts allowed him to study painting and drawing. He entered and placed in many local art competitions, said to be the most awarded student up until that time.

CRANBROOK ACADEMY OF ART, 1937-1943

By the fall of 1937, another scholarship entitled him to become a student, again of painting, at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Cranbrook was, at the time, an eclectic melting pot of creativity attracting many famous artists and designers: Carl Milles, resident-sculptor, Maija Grotell, resident-ceramist, Walter Gropius, visiting Bauhaus-architect, the Saarinen family and others. Students did not receive a degree; rather they discovered their passion. The years at Cranbrook were a momentous turning point in Harry’s life and career.

In 1939, Eliel Saarinen, Director of the Cranbrook, asked Bertoia, age 24, to re-open the metalworking shop. With the war-time need for metal supplies, Bertoia was forced to concentrate on jewelry, which did not use much metal. He shared his hand-crafted jewelry with his friends at Cranbrook and made wedding rings for Ray Eames and Ruth Bacon. The organic shapes and fine detail of the jewelry later evolved into the early sculpture forms.

Harry continued an after-hour activity he had begun as a student, experimenting and producing one-of-a-kind prints and drawings known as monotypes. The monotypes of the 1940s are considered some of his most imaginative graphics. His last year at Cranbrook in 1943 was spent as their graphics instructor (metal supplies were completely consumed by war efforts).

Fellows students at Cranbrook – Florence Schust (Knoll), Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen – were extremely influential to Bertoia’s life in later years. In 1940, Harry met Brigitta Valentiner, the daughter of Wilhelm Valentiner, Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts and the foremost expert on Rembrandt in the U.S. Harry and Brigitta were married on May 10, 1943. Valentiner introduced his son-in-law to such European modernists as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Joan Miró, which had a profound influence on Harry.

While at Cranbrook, Harry Bertoia sent about 100 prints to The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of Non-Objective Paintings for evaluation. To his amazement, Hilla Rebay, the acquisitions director, asked to purchase all 100 prints. She bought some for herself and some for the museum for about $1000. In 1943, 19 of those prints were exhibited by the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation. Harry had the most works by a single artist in that show, which included works by Moholy-Nagy, Werner Drewes and Charles Smith. Supported by a stipend from Karl Nierendorf of Nierendorf Gallery in New York, Harry continued to hold exhibits of jewelry and drawings. Harry designed several sleek tea sets; one for Eliel Saarinen, which is in the Cranbrook permanent collection, and another is displayed at the Detroit Institute of Art.

CALIFORNIA, 1943-1950

In 1943, Bertoia and his new wife departed from Cranbrook to join Charles Eames in California to pursue ongoing experimental work on molded plywood. The plywood work stemmed from a continuation of the Eames/Saarinen Cranbrook chair design that won the Museum of Modern Art organic furniture design competition. The award winning chair could not yet be successfully mass produced, so the mission was to find a way in which to do so. Prior to the chair research, Harry contributed to the war effort making airplane parts manufactured by Evans Products Co, where Eames was director of Research & Development. The Eameses sent Harry to a welding class at Santa Monica City College where he learned the skill that would carry him through life. Harry’s innovative chair solutions made production possible and were adopted by Eames with no credit attributed to Bertoia. In frustration, Bertoia moved on in 1946.

Harry spent two years in San Diego, at Point Loma Naval Electronics Lab, where he worked on a project involving human engineering (we now call it ergonomics) and stroboscopic photography designed to evaluate equipment. In his spare time, Harry was involved with the Allied Craftsmen of the area. By this time, Harry was making jewelry and monotypes and experimenting with early wire sculptures in his spare time. In 1945, Harry held a show of his monotypes at the San Francisco Museum of Art. He became an American citizen in 1946. His daughter Lesta and son Val were both born in California. While struggling to do his art on the side, Harry longed to have the space and time to put his creativity to good use. That opportunity soon came from an old school pal from Cranbrook.

EARLY YEARS IN PENNSYLVANIA, 1950-1960

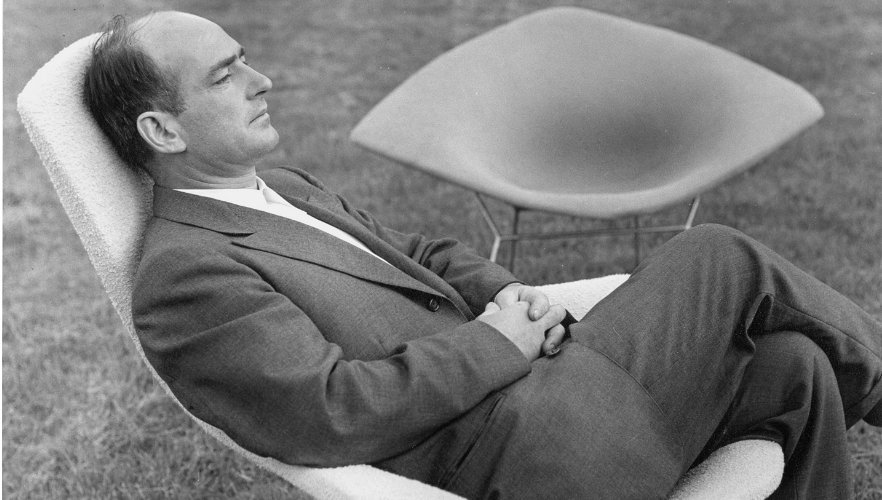

In 1950, at the invitation of Hans and Florence Knoll of Knoll, Inc., Harry moved to eastern Pennsylvania with his growing family. Florence (Schust) Knoll had seen his work at Cranbrook, heard he left Eames, and suspected he had more furniture ideas inside. Being a “metals man,” he came up with a wire grid series of chairs. The Bertoia chair collection was introduced in 1952 by Knoll.

Bertoia also designed the jigs for the production of the items. Harry set up shop in Bally in an old leaky garage building that was acquired by Knoll. The chair became part of the “modern” furniture movement of the 1950s, later referred to as Midcentury Modern. In the span of two years, Bertoia completed several chair designs for Knoll. They compensated him generously for his popular work, enabling Bertoia to put a down payment on the 18th century Barto farmhouse he had been renting, as well as taking over the Bally shop. Daughter Celia was born in Pennsylvania.

The first architectural sculpture commission that Harry earned was in 1953 for the General Motors Technical Center, thanks to architect and Cranbrook pal Eero Saarinen. This set him on a path of highly successful monumental public works, of which he completed over 50. Also commissioned by Eero Saarinen was the altar piece in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chapel, created in 1955. This is one of the most striking sculptures by Harry Bertoia.

In 1957, Harry received a grant from Chicago’s Graham Foundation, affording him the opportunity to return to Italy for the first time since his emigration in 1930. He visited relatives and most of the great Italian museums, reveling in the travels. He never managed to return to Italy again, although he fervently wished to do so. During this period he began earning prestigious awards, which would continue for the rest of his life. The first European exhibit of his sculptural work was at the US Pavilion of the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, alongside Alexander Calder.

In 1956 the Fairweather Hardin Gallery of Chicago began to display Harry’s work and continued to do so for decades. 1959 was the start of Harry’s affiliation with the Staempfli Gallery in New York. Each Staempfli exhibition boasted beautiful color brochures. Knoll also had a continuing warm relationship with Harry, and often displayed and sold his sculptures in their showrooms. Wire landscapes, panel screens, and bundled wire came to life during that time, as well as continuing monotypes. His architectural commissions of the1950s can be viewed here.

During this period, he created multiplane sculptures with small plates of reflective metal, dandelions inspired by the flower gone to seed, bushes that resembled the shrubs around his house, stainless steel bundled wire shapes like willows or pines, and other wire forms often playful but deceivingly complex. See details here.

The monotypes continued, then often acting as a planning device for future sculptures. See more here.

TONALS AND SONAMBIENT, 1960-1969

The 1960s saw prolific production of large scale commissions, working with some of the best known architects of the era. Fountains, huge screens, tall towers, and earthly panels were dotted around the country and even internationally. See details here.

A new passion completely captured Bertoia’s attention, after he heard an accidentally flung wire pinging as it landed. In 1960, Harry Bertoia began the exploration of tonal sounding sculptures. Their sizes vary from a few inches to as tall as twenty feet. Many metals were used for the rods, the most common being beryllium copper known for its wide range of color variations and rich tones. Some rods are capped with cattails, others with cylinders, which, by their weight, accentuate the swaying of the tonal rods and creating deep resonant tones. Harry and his brother Oreste both loved music and spent endless hours experimenting and finding new sounds to incorporate into Sonambient, the auditory and visual environment created by the tonals. See gongs, singing bars and tonals here.

Enjoy sample sounds here.

Harry set up his remodeled barn in 1968-1969 to hold his private collection of 100+ tonal sculptures and act as a sound recording studio. He gave small concerts to lucky visitors and close friends. Bertoia recorded 11 albums of the haunting sounds of sculpture known as Sonambient beginning in 1970 and culminating after his death. The family discovered almost 400 reel to reel Sonambient tapes and has been working on digitizing and releasing these. Our distributor has offerings here. The Sonambient Barn collection remained intact until the summer of 2016 when family decisions prompted important changes. 19 Harry Bertoia sculptures remained in the Pennsylvania barn. A few were sold to support the Harry Bertoia Foundation. The remainder are looking for a public home where concerts might be heard once again by a new generation. In 2022, well-known jazz musicians gathered at Nasher Sculpture Center to incorporate Sonambient into their Avant Gard music, hear it here.

THE LAST YEARS, 1970-1978

Bertoia was selected to do the memorial piece for the Marshall University football team in Huntington, WV, in 1972. The 2006 movie, We Are Marshall, outlines the tragic plane crash. The 6500 pound 13’ high sculpture commemorates the 75 lives taken. The sculpture on the campus of the University has become an iconic symbol to the entire city, attracting weddings, memorial services and picnics. His sculptures, like his person, have a way of sticking with the viewer. They are more than a visual treat; one can almost feel the soul and spirit of the universal wisdom. Sculptures at airports, banks, and universities sprang up during this time. See samples here. as well as numerous one-man shows all over the country, and world. See a list of exhibitions here.

A persistent sore throat and laryngitis led to the diagnosis of cancer in 1977, which caused Bertoia to work furiously on and putting his life’s work in order. He had produced thousands of pieces of art during his short life. He perfected the tonal barn collection, put together a beautiful limited edition monotype book, created the album covers for his upcoming Sonambient long play phonographic albums and sorted through invoices for unpaid works.

His work had consumed most of his time, much of his passion, and ultimately all of his energy. The toxic fumes such as from the beryllium copper he so loved contributed to the lung cancer. Yet, his death was peaceful, he felt complete, and he finally accepted dying as simply one more transitional part of life. Harry Bertoia died at age 63 on November 6th, 1978 in his home.

His wife Brigitta died in 2007 shortly after her 87th birthday. His children Val and Lesta are artists in their own right, while daughter Celia founded and directs the Harry Bertoia Foundation. Harry Bertoia is buried behind the Sonambient Barn in Pennsylvania under a huge 1-ton 10’ Bertoia double bronze gong. See the gong here.