Bronze Sculptures

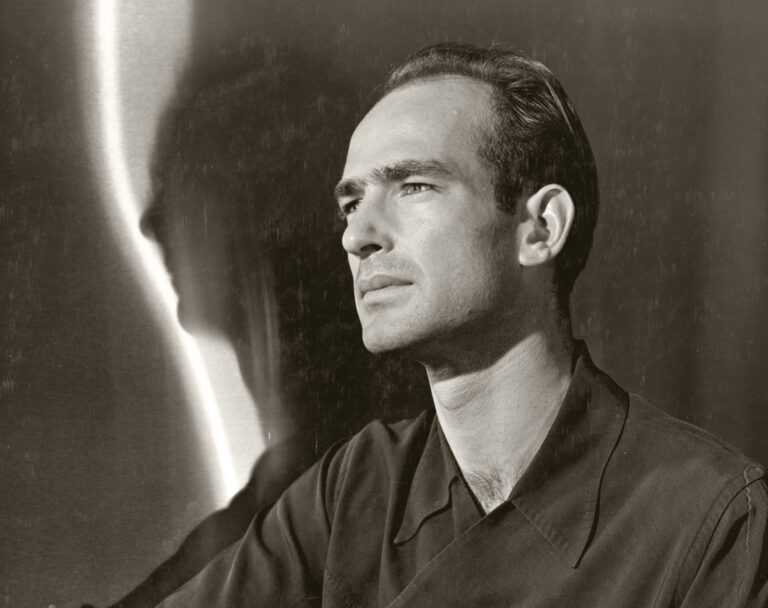

While Harry Bertoia is known for his monumental architectural commissions and impressive sounding sculptures, he also made countless small table top sculptures that offer magical charisma and levity. Harry, the man, was quite charming with his Italian lilt and sparkling blue eyes. When viewing a massive public sculpture, we may be reminded of the artist’s powerful, focused creativity. But today we will examine his lighter more charming pieces, like the man in his more relaxed moments.

Harry’s workshop, or simply “the shop” as he called it, always had a major project in mid-construction downstairs. He produced more than 50 significant public pieces in 25 years, demonstrating his strong work ethic and drive. Yet he found time to make the bushes and tonals that clients requested, and create enough varied sculptures for the next gallery or museum exhibition. But what happened after normal work hours fell into a completely different category. Money-making endeavors claimed the 8 to 5 hours, but experimentation and exploration in welding took over the after-hours period.

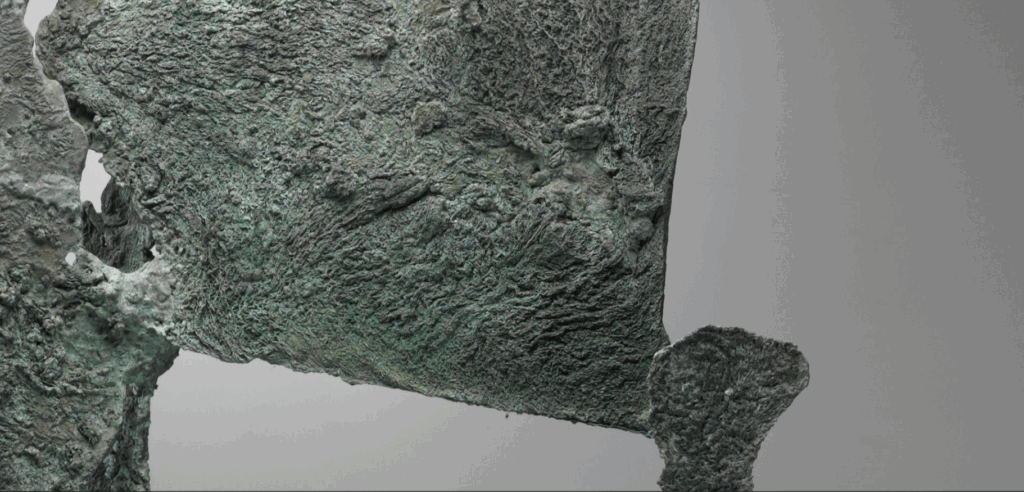

The directly molded bronze forms (and a stainless steel one in the below example) were a few of the experiments made when the artist was alone in the shop. We at the foundation are using the terms in this article (and in our upcoming Catalogue Raisonné) for practical purposes. When the word “mold” is mentioned, one may imagine liquid metal being poured into a mold. Harry very rarely did that traditional technique. We are using the term mold as in forming or shaping the metal. These terms are not necessarily standard to sculpture, but rather are useful in describing Harry’s unorthodox techniques.

Harry used small sections of tonal cylinder rods to create figures and shapes of all sorts. He took the thick rods, heated them to malleability, then twisted, pulled or cut them as desired. “Directly molded” indicates the original metal shape is still detectable but may include severe bending or twisting and cuts. He created many monotypes depicting these forms.

This was when we were still located in Montana, and I knew that they were serious when they came in person to visit the Foundation in Bozeman. Traveling to Bozeman requires strong desire and fortitude! Upon meeting Marin, I immediately enjoyed who she was.

We fondly refer to the above style as “laughing man” although Harry did not name them at all. The above sculptures, while appearing very simple, are actually very difficult to create. The clean straight cut combined with the heat necessary to bend it open while leaving the cut intact is challenging to achieve in one piece. These directly molded pieces were mainly created in the 1960s, but again, as Harry was wont to do, some showed up in the 1970s.

The form below combines several techniques. The near-cube base is simply cut and patinated. The curved shape had to be heated and shaped several times to get the steep curve.

The blunt end is polished to add interest. This form might be considered directly molded as well as melt pressed. This leads into the melt pressed sculptures themselves.

The melt pressed pieces were heated by torch to malleability, then forcibly pressed and pounded into various shapes. They were pressed so strongly or so many times that the original metal shape was no longer discernible. I like to call them “paperweights” and Harry sometimes referred to them as “coins.” It would have to be a very strong person to use them as coins! One of these round flat pieces keeps my papers from blowing around on my desk and I like it very much.

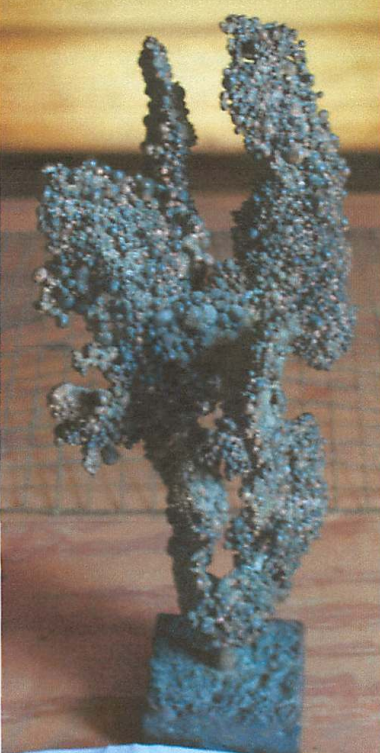

One of the evening ventures in the mid-1960s resulted in forms we call shot fusion. Harry liked to use small beads, about BB pellet size, to create interesting forms. He discovered these shot pellets inside large wooden crates containing the rod supplies he used for tonals. They were leftovers from the process of extruding wires and rods and accidentally landed in the shipping crates. The metal supply companies considered them worthless waste material. Harry explored using these round shots to make fascinating flat surfaces and later as he gained more skill in the unusual technique, other more complex shapes. He liked them so much that he began to order the shot specifically from the metal company, and naturally they charged him for the junk with a newfound use. Harry was, perhaps, one of the first ecologically minded sculptors, as he enjoyed making use of every scrap of metal that came his way.

The shot fusion sculptures are unique to Harry’s oeuvre, as far as I know. I deduce that he initially laid a flat bronze or copper sheet on his work table, and then gently grouped or placed the shot on the flat surface and welded them all together. Some of the box-like shaped pieces were simply several of the flat plates welded together, as above. But others had to be constructed in a different method, as the shape was not at all flat but rather undulating. If any metal workers in our audience read this and have ideas on how these were built, let us know! Somehow, Harry found a way to site each bead on top of the previous ones, possibly by having a very concentrated flame on the torch. At the top, it appears that he positioned single shots in a single line, which had to be an incredibly painstaking process. He sometimes used the word pebbles for the shots as in “bronze pebble tree.” He played around with this technique for several years until he felt he had explored most options, and then let it go.

I can just imagine the fun and delight he must have had during these adventuresome sessions. It might be compared to a photographer who does beautiful artistic wedding pictures for a living by day and wild special effect fantasy-scapes by night for pleasure. Although, in Harry’s case, he loved all of his creative processes! The only thing he disliked was keeping track of money and the paperwork. It was these smaller pieces that were often rewarded to a wayward visitor who showed enthusiastic interest. Weren’t they lucky!?