Gongs

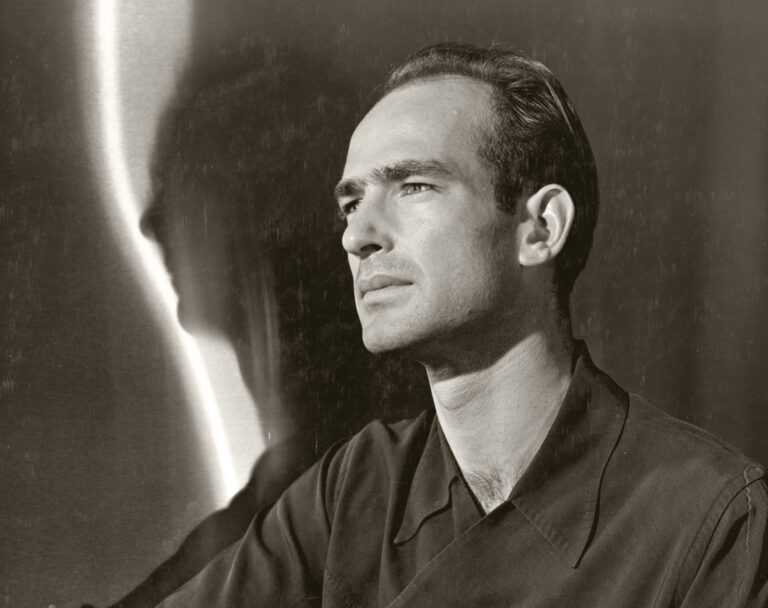

From early on, my father had grandiose ideas about gongs. Several monotypes of the 1960s revealed his dreams of utilizing the Aeolian harp concept in his own sculptures. This never materialized, but was certainly an unrealized vision for most of his career. His gong for the American State Department in Dusseldorf, Germany, was installed in 1956 and was his lone gong for many years.

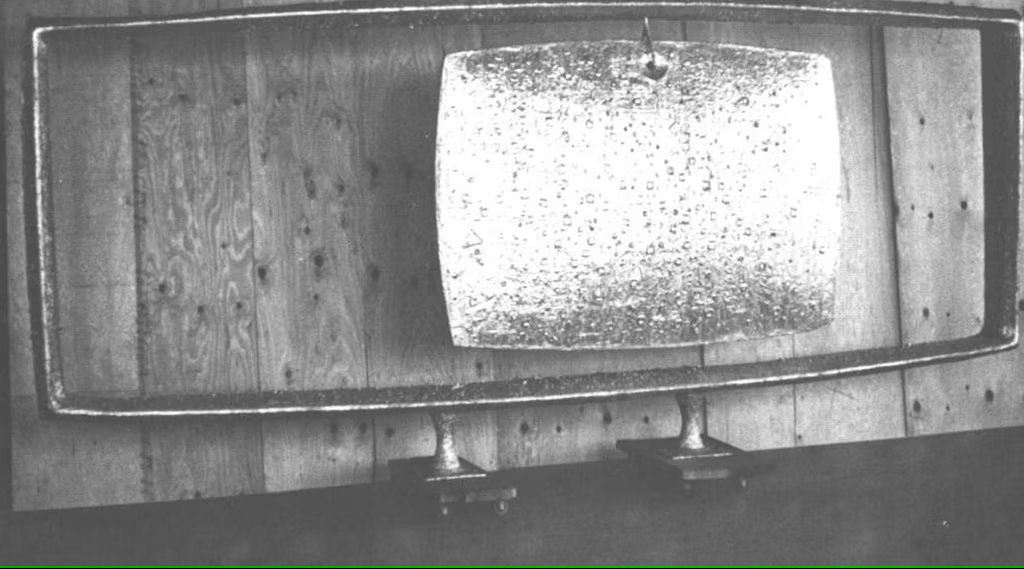

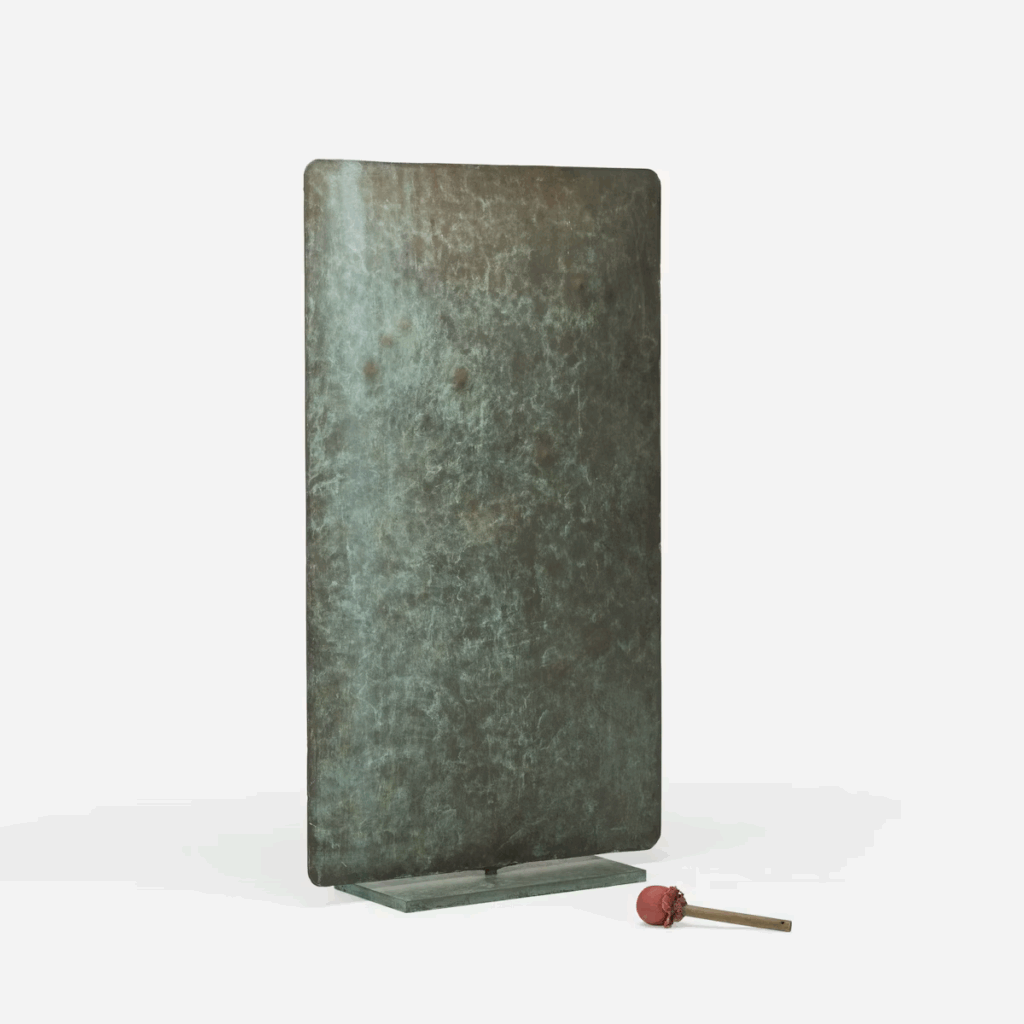

It was a rectangular horizontal shape, not so different from the gongs he created in the 1970s, with rugged texture.

It wasn’t until the sounding sculptures were born that the gongs truly found their place in Harry Bertoia’s oeuvre.

Many monotypes (his platform for brewing ideas) from the the late 1960s and 1970s are filled with gong-like shapes.

In the 1970s the Bertoia gongs as we see them today were born. The exhibitions in Norway, coordinated by Kaare Berntsen, spanning from 1975 to 1978, were the best showcase of his finest and largest gongs. In 1977, Harry concocted numerous miniature gongs that were experiments for a possible limited edition line of pendant jewelry.

Kaare was delighted with the models and wanted to pursue the reproductions, but Harry passed on before the project found completion.

In December of 1977, Minoru Yamasaki and Harry Bertoia were throwing around ideas for one of Yamasaki’s projects. Harry wrote to “Yama,” as he called him, about a large circular gong.

“I always wanted to hang a big circular gong but never found a suitable place to hang it, unless one thinks of Eero Saarinen’s St. Louis Arch or your Twin Towers in New York.”

The largest gong that Harry ever made is just that – a huge circular gong – and measures ten feet, one inch in diameter. It is displayed on the Bertoia estate property in Pennsylvania. Harry himself hung it a few years before his death and it later became his grave marker. We felt it was the best memorial for such a large-minded man.

“Man is not important. Humanity is what counts, to which, I feel, I have given my contribution. Humanity shall continue without me, but I am not going away. I am not leaving you. Every time you see some tree tops moving in the wind, you will think of me. Or you will see some beautiful flowers; you will think of me. I have never been a very religious man, not in the formal way, but each time I took a walk in the woods, I felt the presence of a superior force around me.”

– Harry Bertoia, Oct 9, 1978.

The inscription marking Harry’s grave under this massive 1 ton, 10 foot gong.

The gongs come in all shapes and sizes and types. Some are single slabs of metal that often have a slit cut through half of one side of the gong to essentially extend the piece of metal. The cut gives the gong a different and deeper sound. Some of the shapes seem rather erotic, sensual and womanly. The double walled gongs have air in between two membranes, again giving a varied and more resonant sound.

Patinas and texture vary widely, with protrusions and hand hammering being popular and colors ranging from green to gray to golden. There were a few double gongs, with a diagonal stem holding each gong.

I believe that my father especially enjoyed the tall double gongs partly because they were large enough to envelope him in the sound.

Patinas and texture vary widely, with protrusions and hand hammering, and colors ranging from green to gray to golden.

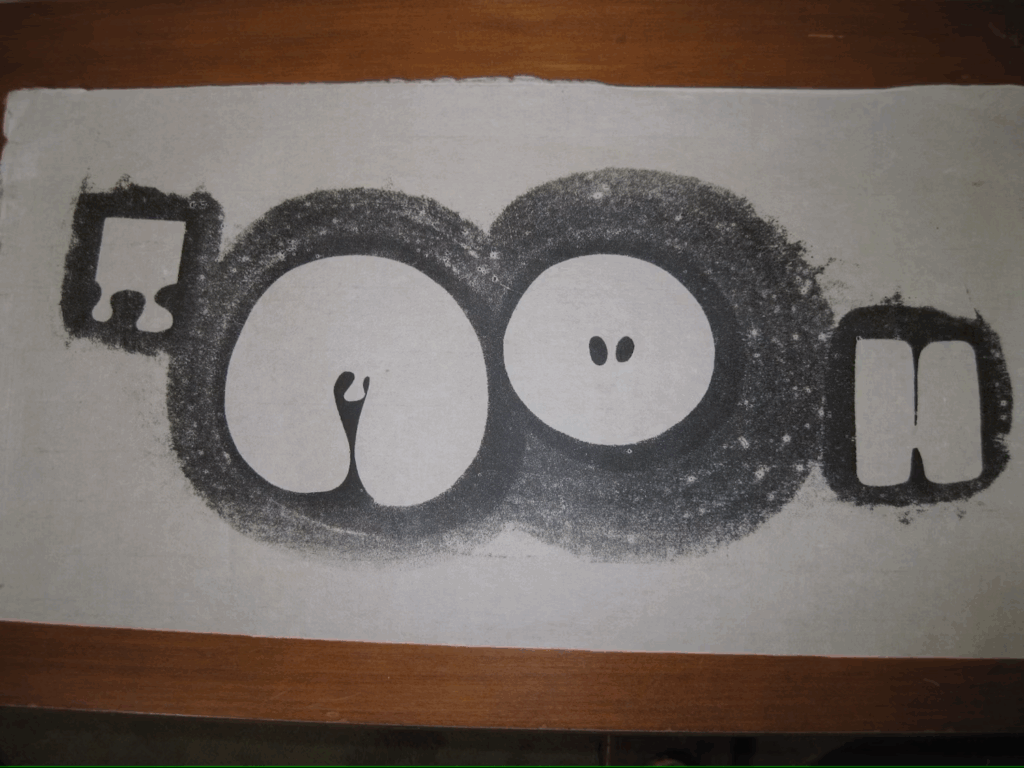

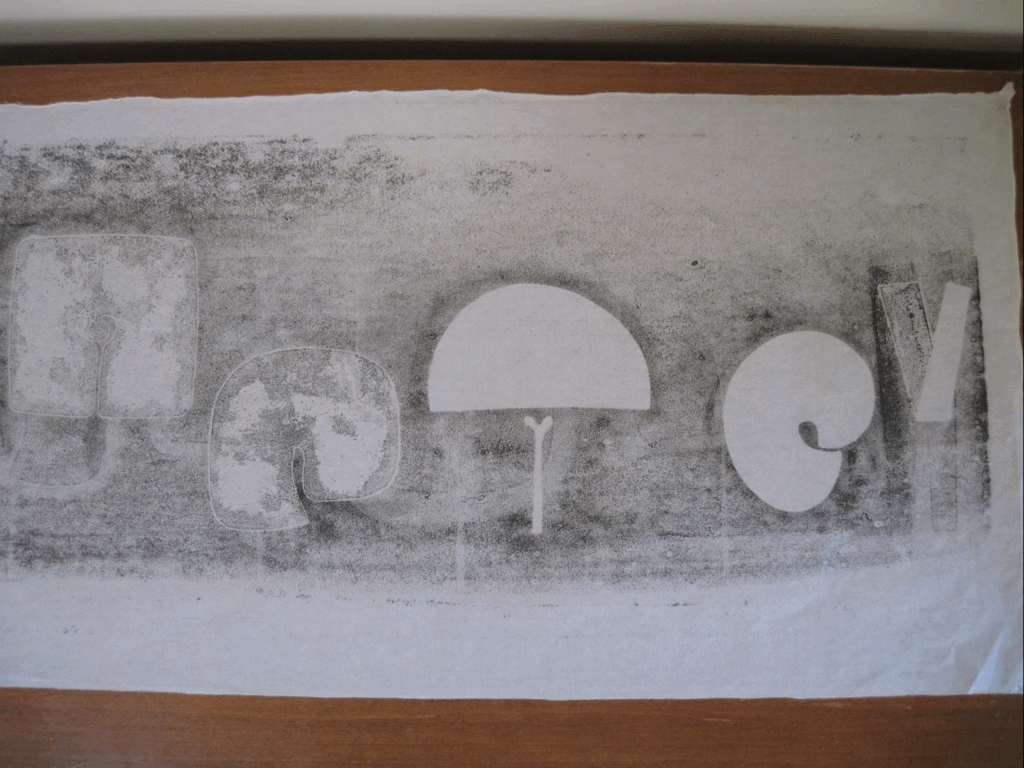

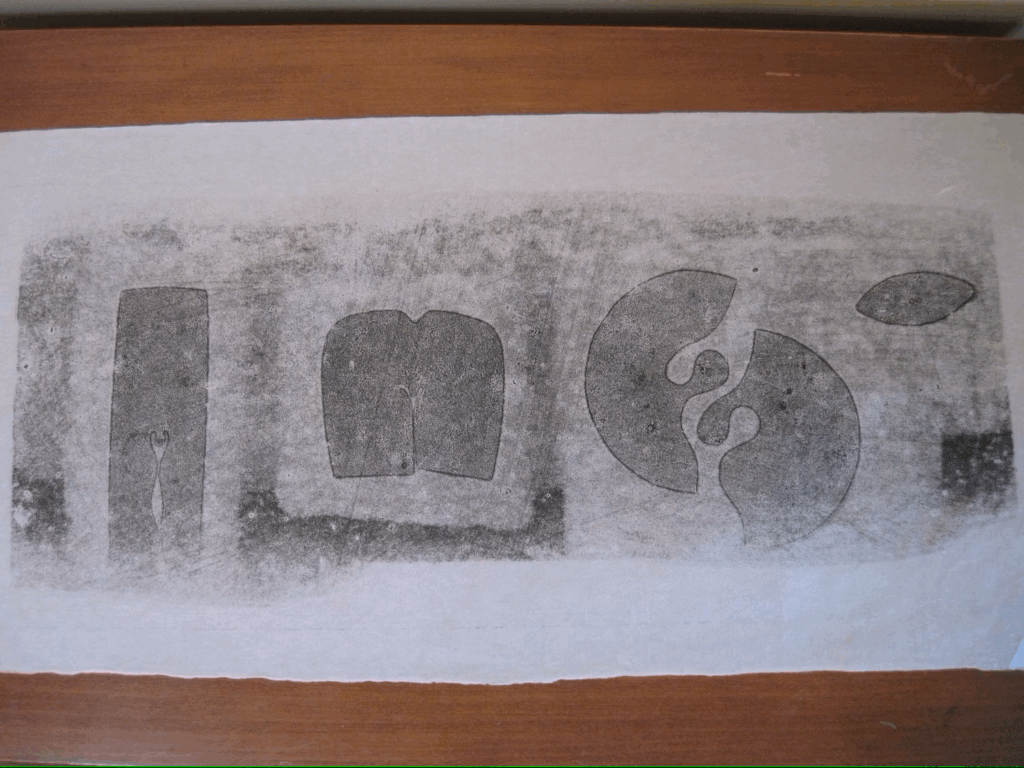

Gong monotype 13 x 25 inches, ink on rice paper. Image © Harry Bertoia Foundation. Numbered by Brigitta Bertoia as #720

Most, if not all, Bertoia gongs have a premeditated method of hanging. A tubular open-ended handle enables an inserted rope or cord to carry the weight of larger gongs. Some have two strategically located holes near the middle through which a rope can be threaded. I’m not sure how he knew where to place the holes so that the gong had the proper slant, but they always seem to hang perfectly. A few have been placed on a base.

Harry usually used a white nylon cord on his own gongs, purchased at the local hardware store, and tied it over a barn beam or a tree. In written directions on how to hang a heavy gong for an exhibition, he suggested the use of thick white nylon rope or stainless steel rope. The gong was to be 24 to 30 inches above the floor. Depending on weight, two anchor points might be needed, ideally as far above the gong as the gong was tall. Thus, for a ten foot gong, the rope should be attached ten or more feet above the top edge of the gong.

I suspect, looking back on it now, that it reminded him of his childhood chapel where the large church bell was rung by means of a clapper.

Gong monotype 13 x 25 inches, ink on rice paper. Image © Harry Bertoia Foundation. Numbered by Brigitta Bertoia as #719

Harry made his own mallets. They varied in their cores from a baseball or softball, to a ball of wound string, to a sock of leather leftovers. They were usually covered with chamois, soft leather or even sturdy cloth, then tied at one end with leather cord. The grip might be a store bought hammer handle or something Harry fashioned himself. Harry called them “clappers.”

We just accepted that a clapper was a mallet back in those days, but I suspect, looking back on it now, that it reminded him of his childhood chapel where the large church bell was rung by means of a clapper.

Harry was all smiles and exclaimed, “I heard it! I heard it!”

Harry once conducted an experiment to discover how far away his ten foot round gong could be heard. He had one of his workers synchronize watches with him, then drive to the property where the gong lived. At the agreed upon hour, Sam pounded on the gong for a few minutes.

The house was about three miles from the shop. When Sam returned, Harry was all smiles and exclaimed, “I heard it! I heard it!” We’re not sure what the neighbors thought, but we never got any complaints.

He often pounded the gongs with his bare fist.

Photo by Jeffrey Eger

During the Sonambient barn concerts, Harry used the gongs intentionally at intervals. He had a method of rubbing certain gongs with a moist thumb or a special small mallet to achieve a whale-like wail. This eerie whine can be heard on the Sonambient recordings.

He often pounded the gongs with his bare fist. Three or four foot diameter gongs added a mellow tone here and there. The huge ten foot vertical gong was often the final crescendo of a barn concert, thundering and moaning for minutes. Its roar filled the entire barn with vibration and experience and resonance. The wooden floor trembled with the gong’s power. It was tremendous!

When Harry devised the term “Sonambient,” he envisioned all of the sounding sculptures – singing bars, tonals and gongs – creating a sound environment.

Photo by Jeffrey Eger

When Harry devised the term “Sonambient,” he envisioned all of the sounding sculptures – singing bars, tonals and gongs – creating a sound environment. Many now use the term interchangeably with sounding sculptures, which is acceptable as a user-made term, but it originally meant more than that.

Harry enjoyed Bucky Fuller’s concept of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts – synergy – and this is absolutely true with Sonambient. While collectors are happy with a few tonals, one really should have a gong to go with it to complete the sound environment.